It’s Not All about the Shoes

Longform

What do we buy when we purchase a pair of sneakers? With an innovative new owner and a very 21st-century way of doing business, iconic brand Reebok—darling of ’80s yuppies and ’90s NBA stars—is hoping it knows the answer.

Illustration by Benjamen Purvis

This is something of a strange question, so please bear with me, I tell Matt O’Toole, Reebok’s fit, athletic-looking president. An affable Midwest native with expressive blue eyes and an easy laugh, he smiles.

Over the past few weeks, I explain, as I’ve worked on this story about Reebok, I’ve learned or been reminded of a lot about the company. Its out-of-nowhere rise to sneaker and athleticwear superstardom in the 1980s. The cultural buzz its shoes and athlete endorsers continued to generate in the 1990s and early 2000s. Its purchase by rival Adidas in 2006. The move from its longtime campus in Canton, 15 miles southwest of downtown, to cool new digs in the Seaport in 2017.

But as I’ve immersed myself in Reebok-world, I’ve also found myself thinking a lot about my own sneaker history—specifically, the kick I got as a kid out of talking my parents into just the right pair of kicks. I still vividly remember, for instance, the first pair of Converse All Stars I got at some point in the ’70s, not to mention my first-ever Adidas Superstars a few years later. And I haven’t completely gotten over the envy I felt when my buddy Tim arrived in my driveway one day wearing an awesome pair of green Puma Clydes.

So, I ask O’Toole, what’s your sneaker story? Who did you wear as a kid?

O’Toole, 59, who’s sporting a pullover with Reebok emblazoned on the front as we talk via video conference one recent morning, brightens. “Wow, that’s such a great question because it was such a hot topic,” he says. “I have three brothers, and the four of us were playing sports growing up in Chicago. I played basketball, and so [I wanted to get] a pair of suede Converse All Stars—I think they were $14.50.

“It’s funny how roads converge. And when Reebok was coming on the scene in a big way in the ’80s, I was wearing Classic Leather”—a Reebok staple from that era—“most of my young adulthood. I had no idea I would end up where I am today.”

O’Toole, who joined Reebok in 2008 after a couple of decades in the sporting-goods business and became the company’s president six years later, shakes his head. “But it’s funny how you remember the things that you either wanted for Christmas or you had to kind of negotiate with your parents how you were going to get.”

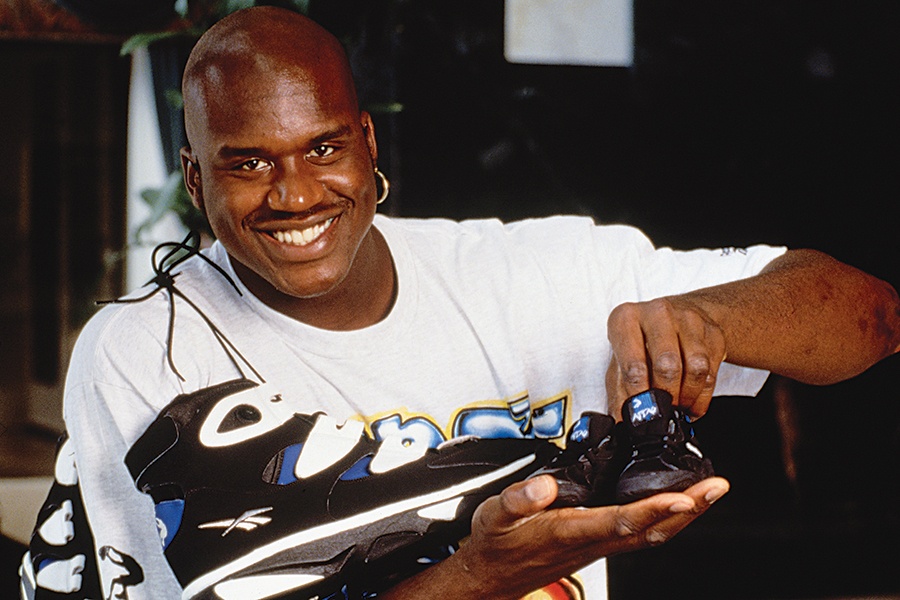

For a long time, atop many people’s sneaker wish lists were any number of Reebok shoes. There was the groundbreaking, female-focused Freestyle, which first put the company on the radar in the go-go ’80s. The innovative Pump, which caused a sensation a few years later. The various “collaborations,” to use sneaker industry lingo, with stars like Shaquille O’Neal and Allen Iverson and Jay-Z. All of them—and plenty of others—helped turn Reebok into one of the most well-known athleticwear brands in the world, while turning the company’s longtime leader, Paul Fireman—a working-class kid born in Brockton—into a billionaire.

But over the past decade, alas, things haven’t been nearly as rosy. In 2006, the year it was acquired by Adidas as part of a strategy to take on leader-of-the-pack Nike, Reebok was among the highest-selling sneaker brands in the world, with a 10 percent market share. Today? It’s tumbled all the way to 16th in sales, and its market share is a barely noticeable one percent. And that’s after a relatively strong performance in 2021.

Despite the gloomy decade and a half, however—and despite the elimination earlier this year of 150 Boston-based jobs—the mood at Reebok HQ these days is cautiously optimistic. Last August, Adidas announced it was selling Reebok to Authentic Brands Group, an innovative, New York–based licensing company that, over the past few years, has acquired and helped resuscitate a range of beleaguered brands, from Aéropostale, Juicy Couture, and Forever 21 to Eddie Bauer, Brooks Brothers, and even Sports Illustrated. Ironically, key to making the deal happen was none other than Reebok’s “collaborator,” NBA legend Shaq, who these days (among many things) is one of ABG’s largest shareholders. The message from the new owners: After 15 years of being constrained by Adidas, it was time once again to “let Reebok be Reebok.”

Can it rebound? The stakes—and the potential spoils—are plenty high. Thanks to the rise of sneaker culture over the past couple of decades and the boom in athleisure clothing, the global activewear market is now worth more than $350 billion. And that’s only going to grow, given that many of us have now permanently traded our office-casual wardrobes for work-from-home-friendly sneakers and sweatpants. Reebok’s fate also means something for Boston. The three brands traditionally most associated with the city—Reebok, New Balance, and Converse (which has actually been owned by Nike since 2003)—not only have roots in Massachusetts, but have all opened eye-catching new headquarters in Boston in the past decade. Meanwhile, ASICS, Puma, Rockwell, and Wolverine Worldwide (which owns Saucony and Keds, among other brands) have also established a presence here. Welcome to Sneakercon Valley.

Whether Reebok can once again capture a bigger chunk of the booming sneaker pie depends on a lot of things, but most especially whether it’s capable of regaining the cultural relevance it had in its glory days. Indeed, the story of Reebok—its rise, its fade, its attempted renewal—is in many ways a case study in “brand,” that mysterious amalgamation of qualities we associate with particular companies and particular things. Yes, we purchase products because of the jobs they do for us. But more than that, we buy what we buy because of how it makes us feel and who it tells the world we are.

Which, come to think of it, is something Matt O’Toole and I have known for a long time.

Current president Matt O’Toole. / Photo by Al Bello/Zuffa LLC/Getty Images

Jay-Z promotes his S. Carter Collection sneakers. / Photo by Andy Butterton/PA Images/Getty Images

ABG, the company intent on liberating Reebok from its dark Adidas period, came into being in 2010, the creation of Canadian entrepreneur Jamie Salter, who got his start in the sporting-goods business north of the border. The vision for the company laid out by Salter and ABG’s president and chief marketing officer, Nick Woodhouse, essentially rests on two related insights. The first: In a world that’s been utterly disrupted by digital technology, where shopping has been untethered from geography and where we spend immeasurable hours scrolling through incalculable images, messages, and stories on our phones, an appealing, recognizable brand matters more than ever. In fact, it might be the only thing that matters. Their second insight: There are scores of companies out there whose businesses are lousy, but whose brands remain well known and well liked by consumers. And in that gap lies large opportunity.

“I knew there were a lot of amazing brands that were locked in a model that didn’t allow them to breathe,” the 53-year-old Woodhouse, also Canadian, tells me when I ask what made him want to join forces professionally with Salter, whom he’s known for 25 years. “And you need to let them. The phrase we use is, ‘Let the brand be the brand.’ If you take them out of the, in some ways, archaic model they’re in—how their stores operate and how they do wholesale—the brand kind of explodes. There are a lot of healthy brands attached to sick businesses.”

It says a lot about ABG’s own business model (not to mention the culture we’re currently living in) that over the past dozen years the firm has not only acquired more than three dozen mostly ailing retail brands, but also the rights to some of the most iconic celebrities in history, including Marilyn Monroe, Elvis Presley, and Muhammad Ali. The point: From a selling-stuff standpoint, there isn’t much difference. A well-known person is essentially a brand, and a well-known brand has a lot of the qualities of a person. So let’s stop making distinctions where there really aren’t any.

Woodhouse, for example, calls Marilyn Monroe “the first influencer” and marvels at the clout she still has despite, you know, being dead for 60 years. “We knew there was a lot of merchandising capability, and we also knew, with the explosion of social media, that there was a great way to get the message of Marilyn out there,” he says. Under ABG’s model, they maintain Marilyn’s brand, but license her name, image, and likeness to other companies that actually make and sell stuff. “We have Marilyn Monroe at Walmart,” he continues—this includes Marilyn-inspired tank tops, travel mugs, and fishnet stockings, all for $15.95 or less—“and Marilyn Monroe at Dolce & Gabbana and Chanel, two luxury brands.” (The latter uses images of Marilyn, a fan of Chanel No. 5 back when she was still alive, in its ads.)

Early on, ABG confined its celebrity deals to famous folks who’d shuffled off this mortal coil, but a few years ago it also started working with celebs who still roam the Earth. First up was a contract with Shaq. But this wasn’t merely an agreement to act as his agent for a small cut of his endorsement deals. No, ABG paid a large sum up front to Shaq to actually acquire 51 percent of him—or at least the public-facing part of him. This means the company now gets more than half of whatever revenue they drum up for him in licensing deals and endorsements. (Woodhouse says they’ve increased Shaq-related revenue five-fold.) Shaq himself has been so tickled with the arrangement that he, in turn, has invested millions back into ABG for a large ownership stake in the company, creating the very meta scenario of Shaquille O’Neal owning a minority interest in the company that owns a majority interest in him.

Why is ABG able to unlock value in brands where others have failed? One key tactic, Woodhouse tells me, is not forgetting about customers who are already big brand fans. Too many companies, he says, contort themselves to capture newer, younger, hipper consumers, which can be fatal if it messes too much with the DNA that established a brand in the first place. As an example of the right balance, he points to Nautica, which ABG acquired in 2018. “We still love the younger consumer, but we also know that Bob in Calgary”—Woodhouse is a Calgary native—“is 40 years old and loves Nautica. A Nautica polo to him is like Prada, and he doesn’t want it to change. I know I have Bob for 20 more years; he’s very loyal to the brand. And there are Bobs everywhere. It’s a giant segment of the middle class in America and around the world.”

To get even more money out of all those Bobs, ABG does a couple of things. First, it invests heavily in digital technology and e-commerce for its brands, because Bob—like everyone else—is glued to his phone and is happy to buy stuff on it. (E-commerce now accounts for 19 percent of retail.) Second, ABG expands the number of products a brand has—Woodhouse calls this improving a brand’s “internal elasticity”—under the theory that if Bob from Calgary loves himself a Nautica polo, he’ll also love a Nautica water bottle and a Nautica umbrella and other stuff that carries the Nautica name.

Of course, perhaps the most crucial part of ABG’s strategy is that the company itself never actually makes—or technically even sells—any products. It’s a licensing company, one that, à la its Marilyn Monroe model, sells other companies the right to make and merchandise stuff under a particular brand’s name. “We like the decentralized model of [partnering with] the best experts that know how to make things,” Woodhouse says. “We’re very involved in the approval of the product. But our financial model is not one where we own or buy inventory. The [licensee] pays us a royalty, and they handle the business operations.”

This is the model that Reebok will now follow under ABG. Last fall, the company began announcing a series of licensing deals with outfits around the globe—many of which work with other ABG-owned brands—that will manufacture, distribute, and sell Reebok products in their own parts of the world. One company in East Asia. Another in India. Another in the Middle East. Even in the U.S., Reebok won’t technically operate Reebok. That will be done by a company called SPARC Group, a joint venture between ABG and Simon Property Group, the giant mall operator. SPARC will handle everything from the sourcing of materials to manufacturing to operating Reebok-branded retail stores and Reebok’s website.

If all of this makes you wonder what, exactly, now happens in Reebok’s industrial-chic headquarters in the Seaport, well, that’s a fair question. Like most sneaker brands, including the Boston-based ones, Reebok manufactures nearly all of its stuff overseas, and its presence here people-wise has never been massive. In 2006, when it was purchased by Adidas, 1,200 of Reebok’s 9,000 employees were based in its Canton headquarters. By the time Adidas put Reebok up for sale in 2021, that number had shrunk to 700, and following January’s layoffs—which came about because of redundancies with ABG and SPARC—the local head count had shrunk to about 450. The workers remaining mostly focus on two things: the design of Reebok products and the oversight of the Reebok brand. As O’Toole says, “Essentially the brand hub is Boston.”

It would be easy to be snarky about this. You mean one of the brightest lights in Boston’s sneaker universe technically no longer makes, distributes, or even sells sneakers? That’s true. But the fact is, those were never really the things that made Reebok Reebok.

Reebok’s Seaport headquarters. / Photo by Robert Merril/Naranja Studios LLC

Reebok’s classic Club C tennis shoe. / Photo via Reebok

Reebok is interesting in that it has not one but two origin stories. Origin Story Number One takes place in 1958, when a pair of brothers living in Bolton, England—Joe and Jeff Foster—officially launched the company as a maker of fine running shoes (“Reebok” is Afrikaans for a type of antelope). The Foster boys might have been young, but they certainly had the right pedigree, given that their grandfather’s business, J.W. Foster & Sons, had been making running shoes since 1895—including the ones worn by Harold Abrahams and Eric Liddell, two Brits who scored gold in the 1924 Paris Olympics and were subsequently immortalized in the Oscar-winning film Chariots of Fire.

That was a nice bit of lore, but it didn’t necessarily help sell a lot of shoes. For its first couple of decades, in fact, Reebok was, in essence, a small brand focused mostly on the U.K. Which leads us to Origin Story Number Two. In 1979, Paul Fireman—a 35-year-old college dropout who was running his family’s outdoor-sporting-goods store, Boston Camping—came across Reebok at a trade show in Chicago. Until the mid-1970s, Converse, founded in Malden in 1908, had dominated the world of American sneakers, but then along came import Adidas and upstart Nike and a handful of other brands (among them New Balance, a Boston-based company that was purchased by Jim Davis in 1972). With the ’70s running boom creating ever more demand for shoes, Fireman was convinced there was room in the market for at least one more competitor, and following the trade show, he paid the Foster brothers $65,000 for the right to sell Reeboks in North America. Just like that, he was in the sneaker business.

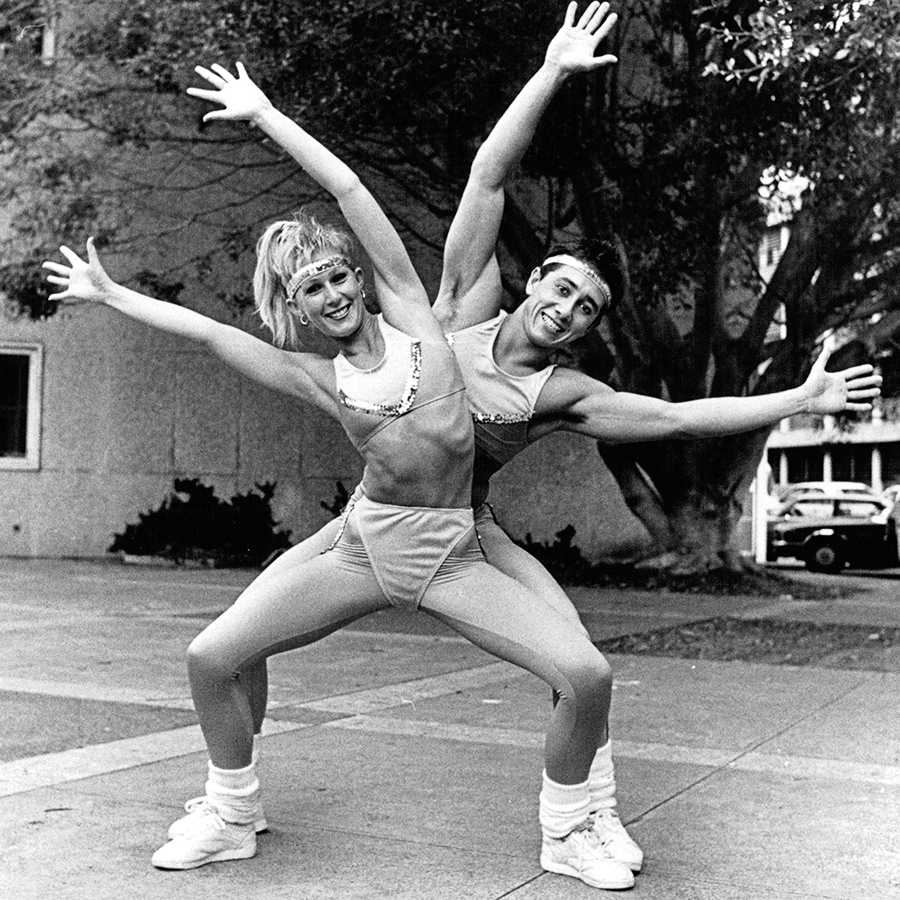

Fireman had marginal success early on with Reebok. But it wasn’t really until 1982 that the brand (pardon the running pun) started to get traction. That was the year that a Reebok employee named Angel Martinez tagged along with his wife to her aerobics class and, noticing that many of the attendees had on either running shoes or no shoes, came back with an idea: What if Reebok were to make shoes specifically aimed at women like his wife? Thus was born the Reebok Freestyle.

From a technical standpoint, there was nothing particularly revolutionary about the Freestyle. Its defining features were a cushioned sole and a soft-leather upper. But from a conceptual and marketing standpoint, it amounted to footwear genius. For starters, aerobics was just beginning to take off, and over the next few years, the Freestyle—and Reebok—would take off with it. More important, the Freestyle was the first athletic shoe specifically geared toward women, arriving at a time when a critical mass of women were finally discovering their fierce athletic sides. “Reebok was a brand with a message at a perfect time for that message,” says Matt O’Toole. “Right on the heels of Title IX, right at this moment when there was ERA and women’s empowerment, Reebok was this brand saying, Hey, it’s okay not only to work out, but to sweat and have muscles and really be physical as a woman.”

Looking back, the growth Reebok had in the mid-’80s is nothing short of astonishing. In 1983, the first full year the Freestyle was available, company sales were $13 million. Just four years later, led not only by the Freestyle but also a tennis shoe called the Club C and the Classic Leather running shoe that O’Toole favored as a twenty-something, Reebok had sales of more than $1 billion and, for a brief moment, surpassed Nike as the most popular athletic shoe in the world.

Crucial to its success was the fact that it had rung the cultural bell. Mick Jagger wore a pair of yellow Reeboks in the video for “Dancing in the Streets.” Cybill Shephard sported a pair of orange Reeboks at the 1985 Emmy Awards. And in cities all across America—including the brand’s hometown of Boston—a generation of career-focused, power-suit-wearing yuppie women could be seen walking to work with Reeboks on their feet. As O’Toole says, “Women really adopted the sneakers not only because they were functional, but because they meant something bigger than that.” The brand position the company had carved out—at the precise nexus of sports and lifestyle—was captured perfectly in an iconic Reebok ad campaign from 1984: “Because life is not a spectator sport.”

Reebok’s rise was so rapid and so of its time that it could easily have been the Miami Vice of sneakers—a here-today, gone-tomorrow phenomenon we’d all chuckle about years later. That it wasn’t is a testament to the creativity, strategic thinking, and marketing savvy of Fireman and his team, who found ways to keep the brand culturally relevant and to expand onto broader turf. In 1989, Reebok unveiled the Pump, the iconic basketball shoe you literally inflated for extra cushion and support. (Celtic Dee Brown pumped up his Pumps throughout his winning performance in the 1991 NBA Slam Dunk Contest.) In the ’90s the company used partnerships with Shaq and Allen Iverson to further establish itself in the NBA, and by the early 2000s it had not only struck exclusive licensing deals with all four major sports leagues, it had also made inroads into hip-hop culture thanks to a partnership with Jay-Z—the first rap star to have his own shoe. “Fireman was a great showman,” says Matt Powell, a longtime sneaker industry analyst. “He could come in and dazzle wholesale buyers. But he was also creative and entrepreneurial. He’d come in Monday morning with 10 ideas that he’d dreamed up over the weekend. Only one of them might be good—the challenge was figuring out which one.”

So what happened? By 2003, Fireman was facing health problems, including heart issues that would require bypass surgery. He was also struggling to find a successor to run the company, cycling through a handful of executives. Finally, in 2005, he accepted an offer that Adidas made for Reebok of $3.8 billion. After the deal closed the following year, he was out. (I called Fireman—who had heart and kidney transplants in 2019—for this story, but after a brief chat he ultimately passed on being interviewed. In recent years he’s been most famous for his house, a 27,000-square-foot mansion he built on 7 acres in Brookline in 1999 and put on the market in 2016 for $90 million. It might be one of the few times he misread the market; it finally sold four years later for only $23 million.)

On the surface, the idea of pairing Adidas and Reebok made sense. Although both were global brands, Reebok was traditionally stronger in the U.S., while Adidas was more robust internationally. By combining forces, the thinking went, they’d be a much more formidable foe against Nike, which climbed to the top of the sneaker heap for good in the 1990s and has dominated ever since. But it didn’t take long before it came clear that the whole of the Adidas-Reebok merger was arguably less than the sum of the parts. “Adidas didn’t do their due diligence,” Powell says. If they had, he explains, they would have understood that the companies operated in vastly different ways.

While Reebok was transactional when it came to dealing with wholesale buyers, for example, cutting whatever deal needed to be cut to get its shoes into stores, Adidas was much more by the book. Quickly there was a realization that the brands weren’t complementing each other but competing against each other, brother against brother, to the detriment of both.

The solution that company management devised was to make Adidas the dominant brand, with Reebok a smaller, more niche player. Reebok was forced to surrender the valuable team-sports turf to Adidas and told instead to focus on the smaller, less lucrative, lower-profile personal fitness market. Adidas was also given the upper hand in marketing deals, and when the retro sneaker phenomenon began several years ago—with customers gobbling up re-releases of classic shoes from sneaker companies’ vaults—Reebok was largely blocked from the practice.

I ask O’Toole if the restrictions ever made him want to bang his head against the wall. He smiles. “In most big organizations there are a ton of opportunities to bang your head against a wall,” he says, before ticking off a few specific headbanging examples from recent years. “Whether we had organized an exciting new partnership with a celebrity, and Adidas felt that would be more beneficial to the company if we could do it on the Adidas platform. Or whether we had a new technology or whatever it might be, these were very frustrating moments for the team.”

From Adidas’ perspective, the arrangement certainly had its benefits. Following the merger, it moved into second place in the U.S. sneaker market, closing the gap with Nike. But for the Reebok brand and brand position, it was crippling. Finally, after pressure from its own shareholders, Adidas made the decision to sell off Reebok. It loosened the reins on some things Reebok could do as a way of improving the bottom line and making it more attractive to potential buyers. Then, in early 2021, it announced it was putting Reebok on the block.

That’s when Shaq, a longtime Reebok partner and partial owner of ABG, got excited. “He was very influential,” Nick Woodhouse says when I ask about O’Neal’s involvement in the Reebok-ABG deal. “Phoning me. Phoning Jamie. FaceTiming every day—You gotta buy Reebok. Every time he did an event with Reebok, he’d walk up to Matt and say, ‘I’m gonna buy Reebok. I’m gonna buy Reebok.’” Woodhouse pauses. “And he’s a powerful guy. Not only is he big in stature, but when Shaq speaks, he’s like E.F. Hutton—people listen.”

The deal was struck last summer, with Adidas agreeing to sell Reebok to ABG for $2.5 billion. That was almost a billion and a half dollars less than Adidas had paid for Reebok in 2006. Of course, the whole thing only made the meta weirdness surrounding Shaq even weirder: Shaquille O’Neal the Man now co-owned a company that not only owned Shaquille O’Neal the Brand, but also the company that had helped make Shaquille O’Neal the Brand so valuable in the first place.

Shaquille O’Neal poses with the fourth edition of his signature shoe, the Shaq Attaq, released in 1995. / Photo by Will & Deni Media Inc./Corbis/Getty Images

Paul Fireman, the former CEO of Reebok, in the company’s ’90s heyday. / Photo by Yunghi Kim/Boston Globe/Getty Images

So what does it mean to “let Reebok be Reebok?”

One thing it means is the release into the world of lots more of those classic Reebok shoes upon which the company built its business and reputation over the decades. Adidas had allowed Reebok to dip its toe slightly into the retro-sneaker waters over the past couple of years as a way of fattening it up for sale, but Woodhouse says they’ve only just begun to go back to the future.

“Nike just keeps bringing the classics out of the closet, and so does Adidas,” he says. “But Reebok really hasn’t. And the Reebok retro vault—it’s sick. It’s almost nutty the amount of shoes we haven’t yet released, but that I know are going to be winners.” He’s right that the retro strategy has been big for other sneaker brands, but it also, conveniently, aligns perfectly with ABG’s go-to strategy of giving longtime brand fans even more of what they already love.

But rebooting Reebok means more than just offering 40-year-old Bob from Calgary a re-released version of the Pump to pair with his Nautica polo. On a grander scale it means re-establishing the Reebok brand and recapturing the powerful brand position Reebok had at its peak. “Reebok is a brand that really lives at the intersection of athletic movement and style,” O’Toole says. “It’s not win at all costs, blood, sweat, and tears. It’s not that brand. But it’s also not a fashion brand. It’s a brand that says, We get it, you’re an athletic person and you have athletic endeavors. But that’s only one part of your everyday life.”

To reclaim that particular space, Reebok is doing a number of things, starting with, on the athletic side of the equation, embracing team sports again. It recently signed NFL star Myles Garrett to an endorsement deal, and one of its big re-releases is the Allen Iverson–endorsed, ’90s-era Question Mid, around which it created as much hoopla as possible at this year’s NBA All-Star Game. And Woodhouse lets on that at least one influential ABG shareholder—you know, the really large guy whose opinion they pay attention to—wants to see them push even harder with the NBA. “I was on a Zoom call with Shaquille this morning,” he says. “And he was like, ‘Never mind retro basketball. How are we going to bring basketball back? Who are we going to sign?’”

On the lifestyle side of the spectrum, the company is reintroducing its iconic “Life is not a spectator sport” marketing campaign, albeit updated for the 2020s. While Iverson—who is 46 and has been retired from the NBA for a dozen years—is prominent in the campaign, he’s also surrounded by younger, more contemporary figures, nearly all of whom are from outside the U.S. and none of whom are athletes. (Among them are Venezuelan musician and artist Arca; British rapper Ghetts; and Nigerian singer, songwriter, and producer Tems.) If it sounds cosmopolitan and cool, that’s the point. “It’s much more of a stew today,” O’Toole says of the people sneaker brands want to partner with. “The athlete’s in there, but there’s a lot of other folks influencing our consumers’ preference when it comes to sneakers and sportswear. The Kanye Wests and Cardi Bs of the world are really big influencers in the sneaker business.”

The presence of the Young and the Musical is a reminder that, for all of its reliance on the classics, Reebok can’t just rerun its playbook from the ’80s and ’90s and hope to succeed. The right kind of celebrity is part of that. So is new technology. But by far the biggest difference between 1985 and 2022 is how brands talk to customers and potential customers. In the old days it was about TV commercials and magazine ads and getting people to walk to work wearing your sneakers. In the digital age it’s about something else entirely: the way you show up in someone’s feed. “Our consumer today is living right here,” O’Toole says, suddenly holding his phone up to his computer screen. “So it’s gotta be in their Instagram feed, it’s gotta be part of what’s happening for them in social media. The brand position and DNA are the same, but the tactics might be different.” To that end, the new version of the “Life is not a spectator sport” campaign features a series of short films that look far more like mini documentaries than ads. Because who clicks on ads?

One other vital difference between the Reebok of the ’80s and the Reebok of today is, of course, its operating model under ABG. Yes, the Boston office will oversee the brand, and it will be the home of the Reebok Design Group, which will be in charge of the global product line. But it will do that with plenty of input from all those licensees that are really running Reebok’s business on a day-to-day, week-to-week basis. That includes U.S. operator SPARC, which interacts in a similar way with several other ABG-owned brands, including Eddie Bauer and Forever 21. “SPARC is headquartered in New York,” O’Toole says. “Eddie Bauer is in Seattle, and they’ve got a [design and marketing team] there just like I described for Reebok. And Forever 21 is in L.A., and they’ve got a team there just like I described for Reebok. So SPARC is at the center of making sure that the brands are operating well inside the U.S. market, but also servicing the global partners.”

As consumers, we don’t see any of this, nor would it matter much if we did. We buy what we like for whatever reason we like it. But there’s plenty of evidence the model works. Last summer, ABG was planning to take its stock public, with analysts estimating its value at about $10 billion. But by the fall, Jamie Salter, Nick Woodhouse, Shaquille O’Neal, and company opted instead to sell a big stake in ABG to a private equity group and a hedge fund. The new valuation of the company: $12.7 billion.

Finalists in the 1987 Reebok National Aerobic Championships. / Photo by Trevor James Robert Dallen/Fairfax Media/Getty Images

A couple of weeks after my video call with O’Toole, I’m standing inside Reebok’s flagship store in the Seaport, staring at a wall filled with classic Reebok shoes like the Club C and Classic Leather. A young salesclerk in a hoodie—it’s technically possible that when these shoes debuted in the ’80s, his parents hadn’t even been born—asks if he can help me. I laugh. “Looking at these makes me feel like I’m back in college,” I tell him.

Truth be told, I was never a Reebok guy. Nothing against the brand—they always struck me as a really good sneaker, and I remember thinking the Pump, in particular, was super cool. But somewhere along the way I gravitated toward Nike, and that’s where I’ve mostly stayed. Call me Bob from Calgary.

What’s interesting to me, as I think about Reebok’s decline over much of the past 15 years, is that it’s had little to do with the quality of what the company has been producing. The brand struggled not because it was making crummy sneakers or guessing wrong on what sneaker consumers wanted, but because it was constrained in telling its story. And a sneaker brand without a strong story might as well not exist at all.

Near the end of my interview with O’Toole, I ask him about the Seaport office space the company moved into in 2017, which is directly above the flagship store. Like most companies, Reebok’s team has spent much of the past two years working from home. Was O’Toole ready to bring people back?

Yes, he tells me. Productivity didn’t fall, but something was lost without people being able to work side by side. “We need an office,” he says. “Especially for a company that, you know—we make stuff. We create prototypes. We have sewing machines and 3-D printers, and this is how we get stuff done. We’re going to need to come together to do that.”

He’s right. Reebok does make stuff. But like all sneaker companies, mostly what it creates are images and feelings and the idea of stuff. Because at the end of the day, that’s what we all love to buy.