40 years after a young mom was murdered with an ax, her husband is arrested. He says he’s innocent, but do his boat shoes tell a different story?

On Feb. 19, 1982, police in the upscale Rochester suburb of Brighton, New York, found the body of Cathy Krauseneck, 29, dead in bed with an ax lodged in her head. She seemed to have died instantly and from a single blow. Downstairs, there were signs of what they believed to be a staged burglary.

Monroe County District Attorney’s Office

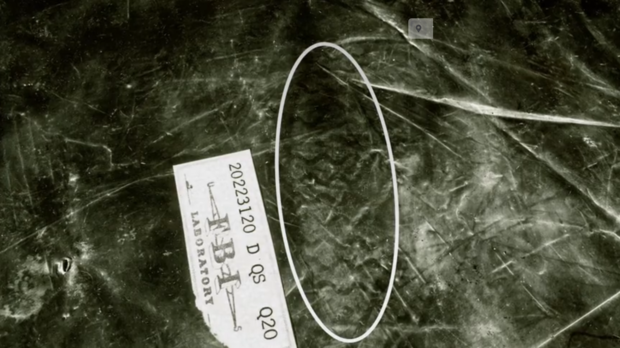

The back door had a single broken windowpane and there was a maul, a type of heavy ax, leaning against the wall. Cathy’s purse and its contents were strewn across the dining room floor in a way that, to authorities, seemed almost deliberate. And there was a silver tea set carefully arrayed on the floor nearby. Next to the tea set investigators found a garbage bag with a faint shoe print inside – as if someone had stood in it to hold it open. Detectives now believe it was an important clue to solving the case.

At first glance, it looked like someone had pushed the pause button on a burglary. But the scene lacked one of the most important hallmarks of a burglary, retired Brighton Police Detective Mark Liberatore and Detective Steve Hunt tell “48 Hours” correspondent Erin Moriarty in “The Brighton Ax Murder,” airing Saturday, Feb. 25, at 10/9c on CBS and streaming on Paramount+.

That’s because they say nothing was taken.

“There’s an officer involved in this case from the 1980s … who hits the nail on the head,” says Liberatore. “We in Brighton do not handle a lot of homicides. We do handle a lot of burglaries … and this was not a burglary.”

Monroe County District Attorney

Back then, investigators suspected the scene was staged by Cathy’s husband, Jim, to conceal his real intention —killing her. Crime scene photos show a pair of boat shoes, like he was known to wear, by her bed. Forty years later, detectives believe the faint shoe print in that garbage bag was made by those boat shoes.

“He’s a boat shoe wearing guy,” says Hunt. “And we don’t have murderers running around in February in the wintertime wearing boat shoes and killing people.”

But the boat shoes next to Cathy’s bed were never tested to see if they matched that print and the original investigators hadn’t kept the shoes. Jim Krauseneck’s lawyer says his client didn’t kill Cathy — he loved her.

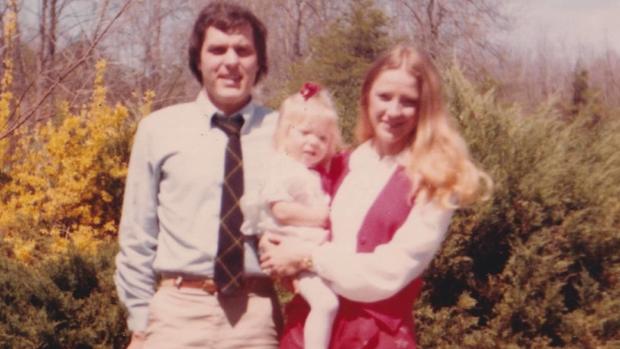

Annet Schlosser

Cathy and Jim Krauseneck and their 3-and-a-half-year-old daughter Sara had moved to Brighton in 1981, just six months before the murder, so he could start work as an economist at Kodak. The day Cathy died, he had told police he’d left for the office as usual, at about 6:30 a.m., and found her body when he returned just before 5 p.m.

To first responders like Bill Flood, it had seemed clear that Sara had been in the house alone, possibly for hours, with her mother’s body.

“She had several sweaters on. They were misaligned with the buttons,” says Flood, who spent 38 years with the Brighton police, before retiring in 2011. “She had several pair of socks on. It was obvious to us she had dressed herself.”

Sara would tell investigators that she had seen a “bad man” with long blonde hair “sleeping in mommy and daddy’s bed with an ax in his head.” Asked if the man was black or white, she said he was “many colors.” Flood thinks Sara hadn’t seen a man at all. It was her blonde mother in bed, covered with blood.

“What does a 3-and-a-half-year-old do?” wonders Gary Craig, a reporter for the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle who covered the case. “It’s inconceivable enough that somebody could take an ax to their wife’s head, you know, if Jim Krauseneck did. But then it’s even more inconceivable to me that you could just go about your workday and leave your daughter in the house with a murdered mother.”

But authorities became more suspicious of Krauseneck when they found a pamphlet in the family car offering marriage counseling and other therapies. And when they talked to people at Kodak, they discovered Krauseneck had been dishonest in applying for the job that had brought the family to Rochester. He’d claimed to have a Ph.D. when he really didn’t.

Still, without more evidence of a motive or anything directly tying Krauseneck to the crime, authorities in 1982 declined to charge him and the case went cold. It would stay cold for nearly 30 years. Then, in 2015, the FBI offered to help with funding and facilities to reopen cold cases and Brighton police asked detective Liberatore to take another look at the Krauseneck case. Liberatore chose Hunt to help him.

There had been some fibers and other prints around the house, but in 1982 they hadn’t shed light on the case. And there hadn’t been much other forensic evidence for original investigators to work with, in large part because DNA wasn’t yet being used as a crime-fighting tool.

But sifting through the boxes of evidence decades later, Liberatore and Hunt agreed Jim Krauseneck was their prime suspect. And they paid him a visit. In April 2016, they flew to the Seattle area, where he was by then living after having remarried. They showed up unannounced, hoping to get a confession. But they left without one.

Lacking a breakthrough with Krauseneck himself, authorities two months later sent crime scene evidence to an FBI lab, hoping new technology might yield new clues. The FBI was able to test a host of items for the presence of DNA and when the results came back, they showed nothing to suggest anyone besides the Krausenecks had been in the house the night Cathy died.

To investigators, this amounted to some of the strongest evidence yet against Jim Krauseneck.

“It sorta (sic) became … who else could it be?” says reporter Gary Craig.

Still, to prove Krauseneck had killed Cathy, DA Sandra Doorley wanted to ascertain as closely as possible what time she had actually died.

“We needed a definitive time of death,” says Liberatore.

That piece of information had always been missing from the Krauseneck investigation. Time of death is notoriously difficult to measure scientifically. The most the 1982 medical examiner had reportedly been able to do was narrow it down to between 4:30 a.m. and 7:30 a.m. Since then, other experts agreed it was impossible to say if Cathy died before or after 6:30 a.m. — the time her husband said he left for work.

But in 2018, prosecutors and police sought yet another opinion — this one from Dr. Michael Baden. Over the course of a 50-year career, Baden has been consulted in a “who’s who” of whodunit cases, from the assassination of JFK to the reported suicide of disgraced financier Jeffery Epstein, often raising eyebrows and generating controversy.

In this case, using the same file from 1982, Baden said it appeared Cathy Krauseneck died around 3:30 a.m. and said in his report “to a reasonable degree of medical certainty … that Mrs. Krauseneck died hours before 6:30 a.m. on February 19, 1982.” If true, that put the murder hours before Jim said he’d left for the office.

“Some people may say that we were looking … for an opinion,” says DA Doorley. “That’s what the defense says,” Moriarty replies. “Absolutely,” says Doorley.

“If, in fact, Dr. Baden had agreed with the other medical examiners … that you can’t precisely pick time of death, would you have hired him?” Moriarty continues. “Absolutely not,” Doorley replies.

Armed with Baden’s opinion — and the DNA test results showing no proof anyone else had been in the Krauseneck house that night — prosecutors put the case to a grand jury, which, in November of 2019, charged Jim Krauseneck with murder.

But Krauseneck’s defense team insists Dr. Baden’s time of death findings cannot be trusted. At Krauseneck’s trial in 2022, they called Medical Examiner Barbara Maloney to the stand. Maloney says the original medical examiner was correct that time of death couldn’t be narrowed down the way Baden had.

“So, you’re saying Dr. Baden is wrong?” asked Moriarty. “I’m saying I disagree with him. I think he is wrong,” Maloney replies, saying that in her opinion, Cathy could have been killed as late as 1:30 p.m.

What’s more, Jim Krauseneck’s attorney Bill Easton argues Cathy’s killer is someone else police were familiar with.

“If Jim Krauseneck didn’t kill his wife, who did?” asks Moriarty. “Laraby!” says Easton.

He says police received an anonymous tip soon after the murder about a serial predator named Edward Laraby, who was living only a half mile from the Krausenecks at the time. Laraby had a long record of attacks against women and when police approached him, he angrily dismissed them, telling them to call his lawyer. Investigators placed the call, but apparently did not follow up.

In 2018, soon before dying in prison on other charges, Laraby confessed to killing Cathy Krauseneck. But Doorley believes he knew he was on borrowed time and simply wanted to negotiate for more privileges in his final days.

“His confession didn’t match up to the facts,” she says.

Doorley says Laraby had described Cathy as having dark hair —she was blonde— and also confessed he had sexually assaulted her. But there was no evidence of that.

Doorley insists she has “absolutely no doubt that Jim Krauseneck killed Cathy Krauseneck that day.”

And the jury agreed.

Shawn Dowd/Pool

On Sept. 26, 2022, Jim Krauseneck was convicted of the second-degree murder of Cathy Krauseneck. The 71-year-old was later sentenced to 25 years to life. Looking on in dismay was Krauseneck’s now-adult daughter Sara, who told the court: “My mother’s killer got away with her murder, and my father’s life has been taken by a failed justice system that convicted him of a crime he did not commit.”

Also attending the trial was Jim Krauseneck’s current wife, Sharon, who insists he has been a gentle, loving partner since they married 23 years ago.

“I know he did not murder his wife,” she says. “When you’re married to a man, you know his heart and you know his soul.”