Brooks Claims Puma Lacks TM, Patent Rights in Nitro Lawsuit

Brooks is pushing back in opposition to the trademark and layout patent infringement lawsuit waged from it in July by Puma, in which the German sportswear brand name claims that Brooks is not only infringing its NITRO trademark by providing sneakers bearing that mark but goes even more by adopting “every aspect” of a sneaker for which PUMA has a style patent in furtherance of what PUMA phone calls a bigger “pattern of [Brooks of] copying [its] engineering and disrespecting [its] intellectual house legal rights.” In the respond to that it lodged with a federal court docket in Indiana on September 28, Brooks denies Puma’s infringement allegations and sets out a handful of counterclaims, in search of declarations from the courtroom that it is not infringing Puma’s alleged trademark rights and its style patent, and angling to get Puma’s patent invalidated.

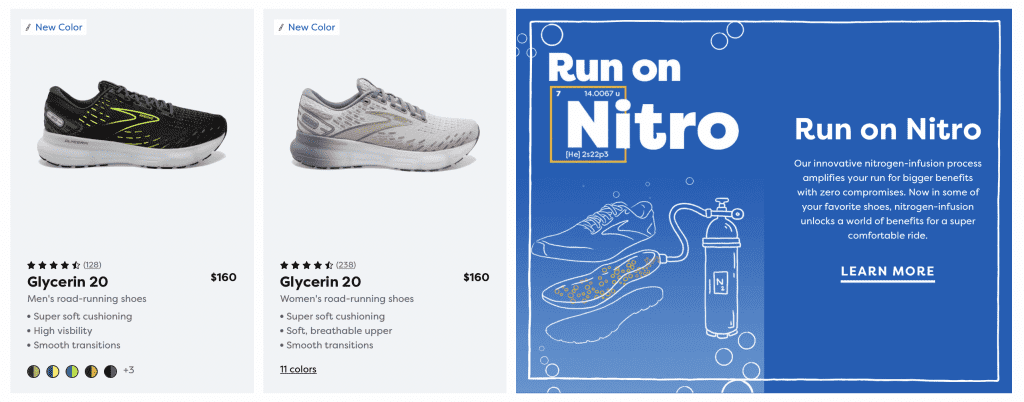

On the trademark entrance, Brooks aims to chip away at Puma’s infringement claim, arguing that “Puma asserts that its selection to name its line of nitro-infused midsole sneakers ‘Nitro’ offers [it] the proper to reduce Brooks from applying the word ‘nitro’ to describe Brooks’ previously-introduced, nitro-infused midsole shoes.” Puma “is wrong,” in accordance to Brooks, which statements that “Puma has no rights to the term ‘nitro,’ which it works by using in a descriptive method, and it surely has no legal rights to protect against Brooks from working with ‘nitro’ to describe Brooks’ possess nitro-infusion technological know-how.”

Seattle-headquartered Brooks asserts that not only does Puma absence a trademark registration for “Nitro” (it submitted trademark purposes in December 2021), its use of “nitro” on its assortment of nitro-infused midsole sneakers is descriptive, and Puma “has not acquired any secondary indicating in the mark.”

Even if “Puma’s use of ‘Nitro’ was not descriptive (which it is),” Brooks argues that Puma – which commenced offering up its “Nitro” sneakers “in or all around 2020, at minimum a calendar year right after Brooks 1st released nitro-infused midsoles” – “would have no priority and no enforceable rights in ‘nitro’ for working sneakers or apparel, [as] numerous other functioning shoe organizations, like Brooks, applied the term “Nitro” for working footwear prolonged in advance of Puma.” Brooks claims that it very first provided a shoe called the “Nitro” shoe in 1998, and considering that then, no scarcity of other models – from Nike and adidas to Saucony and Asics – have provided up managing footwear below the Nitro name.

(Brooks also notes that the U.S. Trademark and Patent Business “has consistently rejected attempts [by other companies] to sign up ‘nitro’ as a trademark for nitro-infused goods,” with examiners for the trademark office conveying that “nitro” is “a descriptive shorthand phrase for ‘nitrogen,’ that ‘nitro’ is not distinctive to the nitro-infused items of any a single firm, and that ‘nitro,’ hence, cannot be registered as a trademark when used in connection with nitro-infused items.” The “same result holds true” for Puma and its nitro-infused footwear, Brooks contends.)

Past Puma lacking trademark rights in “nitro,” Brooks argues that it is not applying the term as an indicator of supply of its sneakers, stating that “none of [its] nitro-infused shoes are named or labeled as ‘nitro’ or just about anything very similar.” Alternatively, Brooks statements that it works by using the time period “nitro” exclusively “to describe the nitro-infused engineering in its merchandise.” This is major, as a effective infringement assert requires “use” of a trademark – in a trademark potential – by the allegedly infringing get together.

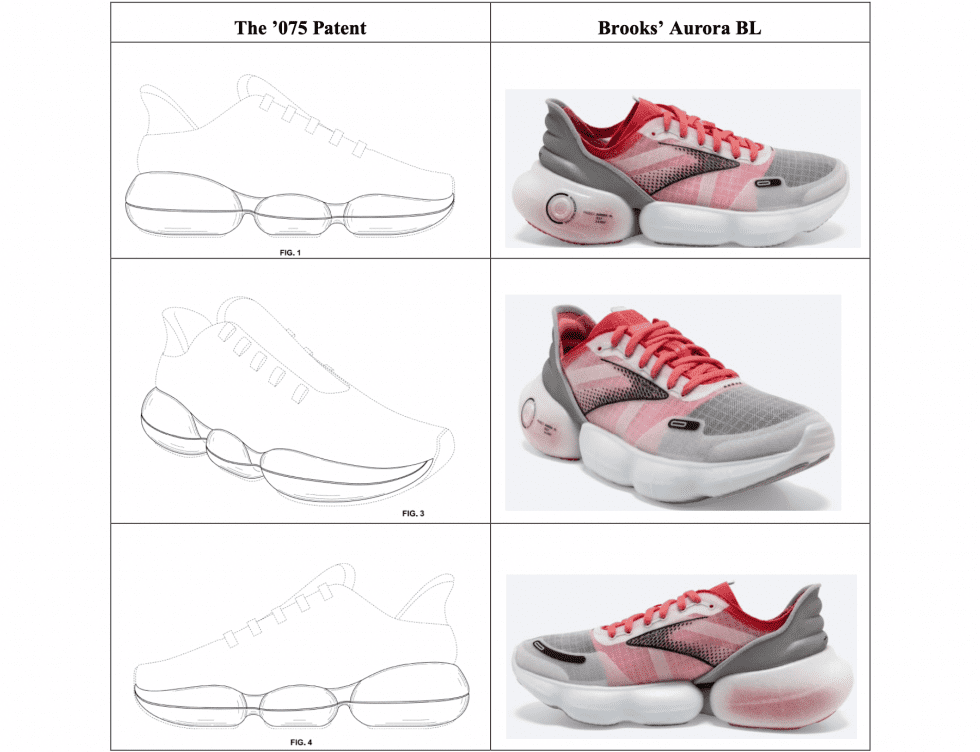

As for Puma’s layout patent infringement claim, Brooks claims that Puma’s allegations – which center on its D897,075 patent, namely, “a solitary assert directed to the midsole of a shoe” – are “meritless,” as the D075 patent design and the structure of its Aurora BL sneaker are “plainly dissimilar.” And the “numerous, promptly-apparent differences in design” amongst the patent design and style and the Aurora BL make it so that “an regular observer would not confuse the all round design and style of the Aurora BL with the total design of [Puma’s] D075 patent,” according to Brooks.

Though “no regular observer, supplying these kinds of notice as a purchaser ordinarily offers, would confuse the two designs” (i.e., the normal for gauging design patent infringement), Brooks asserts that there is an even much more fundamental problem: Puma’s patent is invalid. “In addition to being mostly practical somewhat than decorative,” Brooks argues that “the design in the D075 patent is not novel and is noticeable about the prior artwork,” these types of as several Nike Air Max variations and Balenciaga’s sizzling-promoting Triple S sneakers, between other individuals. Brooks claims that “Puma omits illustrations of prior artwork soles that would further more lead the everyday observer to conclude that the variances among the layout of the Aurora BL and the claimed style have been important, and that the styles have been dissimilar.”

With the foregoing in mind, Brooks suggests that it is entitled to declaratory judgments, such as a judgment that Puma has no legal rights in “Nitro” for use on footwear a judgment that it is, as a result, not infringing Puma’s alleged “Nitro” mark and a judgment that it is not infringing Puma’s D075 patent mainly because “in the eye of an common observer … the style and design claimed by the patent and Brooks’ accused product or service are not ‘substantially the same’ these types of that ‘the resemblance is this sort of as to deceive these an observer, inducing him to order 1 supposing it to be the other.’” Brooks is also trying to find a judgment as to the invalidity of Puma’s patent on the grounds that its fails to satisfy the statutory necessities for patentability.

And still but, Brooks is also in search of an order dismissing the complaint with prejudice, alongside with a discovering that this scenario is excellent, and that acceptable attorney’s expenses and expenditures really should be awarded as a outcome.

Not basically an isolated instance, Brooks argues in its reaction that the Puma lawsuit is component of “a globally campaign on its rival’s part to bully Brooks into abandoning use of ‘nitro’ to describe its nitro-infused midsole engineering.” Exclusively, Brooks states that Puma has “brought emergency motions for injunctions from [it] … in several international countries … primarily based on alleged licenses to ‘Nitro’ that Puma promises to have attained from non-footwear businesses.” Puma has “even long gone so much as to test to freeze Brooks’ European bank accounts, purportedly in purchase to preserve the availability of dollars damages,” Brooks asserts, “even however Brooks is an proven intercontinental organization and a Berkshire Hathaway subsidiary, and Puma’s damages declare, by its personal account, totaled only 150,000 Euros.”

“None of Puma’s aggressive methods has succeeded,” Brooks promises, asserting that “no court in any country has granted an injunction in opposition to Brooks, and German courts have currently twice rejected Puma’s request for an ex parte injunction on the basis that ‘nitro’ is descriptive of Brooks’ and Puma’s technological know-how.” Towards the background, Brooks contends that it “will not be intimidated by Puma’s initiatives to implement invalid intellectual property legal rights or to avoid [it] from properly describing its modern nitro-infused midsole engineering,” which is why Brooks suggests that it is bringing its counterclaims.

Not confined to its respond to and counterclaims, Brooks Sports activities also lodged a motion to transfer the location of the Puma lawsuit out of the U.S. District Court docket for the Southern District of Indiana the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington on September 28, arguing that “there can be no dispute that venue is good in W.D. Clean.” because, between other issues, “Brooks is included and headquartered there, and so ‘resides’ in W.D. Clean,” and W.D. Wash. is “no fewer effortless for Puma than this District, considering the fact that Puma is located in Massachusetts and does not allege a existence in this District.”

The situation is PUMA SE, et al. v. Brooks Sporting activities, Inc., 1:22-cv-01362 (S.D. Ind.).