How the swoosh has shaped the running world

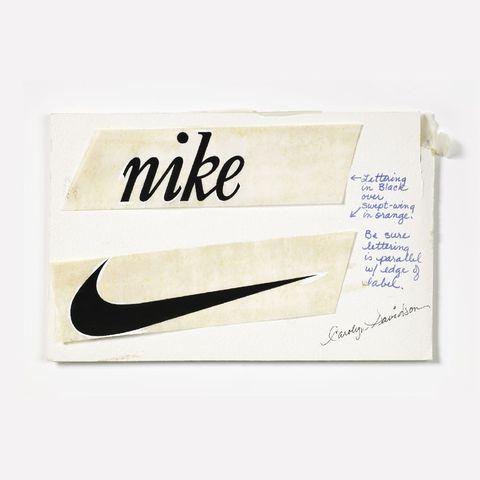

Fifty years after the birth of Nike, it’s impossible to imagine the running world without it. From record-breaking shoes to Olympic kit, via running crews and online ads, the swoosh is everywhere. And yet, implausible though it now seems, the Nike story began, unpromisingly, with a piece of college homework. In 1962, former college runner Phil Knight, finishing his MBA at Stanford, handed in a thesis on Japanese shoe companies being poised to enter the US. It’s not an obvious eureka moment. The Second World War is a fresh memory, and hostility to Japan lingers. So when Knight decided to pack a rucksack, fly to Japan and persuade a shoe company to let him import its shoes, it must have seemed like lunacy.

That, though, was the beginning of Nike, or rather of its precursor, Blue Ribbon Sports. Importing ‘athletic’ shoes from Onitsuka (later to become Asics), Knight sold them not with the slick campaigns and celebrity endorsements that would later follow, but from the back of his car, bankrolled by money borrowed from his exasperated dad.

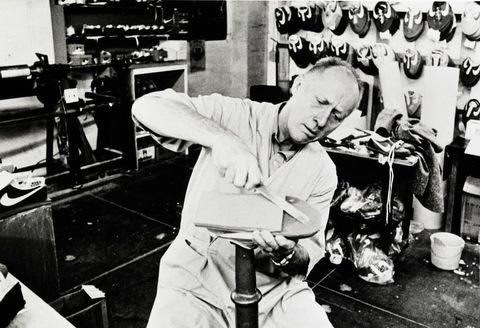

But if Knight’s self-proclaimed ‘crazy idea’ seemed foolhardy to most, it didn’t to Bill Bowerman. The legendary coach had put Knight through his training paces on the University of Oregon track team, and Knight knew about his obsession with running shoes all too well. ‘Bowerman was constantly sneaking into our lockers and stealing our footwear,’ Knight recalls in his autobiography, Shoe Dog. ‘He’d spend days tearing them apart, stitching them back up, then hand them back with some minor modification, which made us either run like deer or bleed. Regardless of the results, he never stopped… He always had some new design, some new scheme to make our shoe sleeker, softer, lighter.’

It’s now 50 years since Blue Ribbon became Nike, yet that description – with its obsessive attention to detail – could have been written today. Bowerman was a design innovator – and a whole lot more besides. In 1967, he published a slim, rather unpromising-sounding volume titled Jogging. Its fundamental message was simple: if you have a body, you are an athlete. It sold millions. Before long, in Knight’s words, ‘Running was no longer just for weirdos. It was no longer a cult. It was almost – cool?

The birth of the cool

‘Almost cool’ soon became ‘very cool’, in large part thanks to a kitchen gadget. At breakfast one morning in 1971, Bowerman was mulling over the perfect balance of spring and grip. He found his gaze drifting over to the grid pattern on his kitchen’s waffle iron, so he took it to the garage and filled it with some toxic chemical mix – and promptly destroyed it. But Bowerman was not the type of man to quit. Several experiments later, he had come up with his sole-shaped waffle design. He sewed it on to a pair of running shoes and gave it to one of his runners, who ran like the wind. And so the Waffle trainer was born – later nicknamed the ‘Moon Shoe’ because the footprints it left behind resembled those left on the soil of the moon by Apollo 11 astronauts. Twelve pairs of the prototype were initially made for runners at the 1972 Olympic trials, but just a year later, a more refined commercial version was released. By 1974, it had built a reputation as America’s favourite training shoe. Such is its remarkable status in running history, that in 2019, an unworn pair of those first prototype Waffles sold for nearly $500,000 at auction.

But the Waffle isn’t just another footnote in running history – it was also one of the first pieces of athletic wear to cross from function to fashion. ‘It didn’t just feel different or fit different – it looked different. Radically so,’ recalled Knight. And then, his innate marketing genius spotted something that was set to change Nike’s fortunes forever. ‘Watching that shoe evolve… from popular accessory to cultural artefact, I had a thought: people might start wearing this thing to class. And to the office. And the grocery store. And throughout their everyday lives …’

And so Knight gave the order: factories were to start making the trainer in blue, which would go better with jeans. Such a simple idea, so obvious in retrospect. But arguably, that is the moment when running gear as fashion really began. Soon after, Hollywood superstar Farrah Fawcett was pictured skateboarding in a pair of Nike Cortez – one of the new Nike shoes ‘providing advanced shock absorption at the heel’. What Fawcett wore was instantly fashionable – and Nike became a household name.

Air to the throne

The Waffle’s design, with a unique outsole combining grip and bounce, was a step change in running shoe design. Not long after, another game changer arrived. In 1979, Nike released the Tailwind, advertised as ‘the shoe with air – captured in the permanently inflated midsole channels’. Developed by a former Nasa engineer, Marion Frank Rudy, the Air technology replaced traditional EVA soles with gas-filled pouches. Unlike in the now-familiar Nike Air shoes, those pouches or bubbles were not designed o be visible to the outside eye – that idea came with the Nike Air Max 1 in the 1980s. But it was with the Tailwind that this new cushioning concept was born.

The Tailwind – which runners loved, but which suffered some technical setbacks – led to super-light marathon shoe the Eagle, and in 1981 to the Mariah, the first racing shoe featuring the ‘Air-Sole: channels of pressurised gas… encapsulated within a polycushion midsole, providing a cushion of “air” which absorbs and redistributes the energy generated with every foot strike.’

Although the Mariah and its technology was a hit, it was one within a limited market of serious road racers. Racers and the fashion-forward might be happy – but with the running boom showing no signs of slowing, a mass-market shoe was clearly needed. So, in 1982, the Nike catalogue offered a new design, priced at $50, intended to work for as broad a range of runners as possible. This new shoe featured an ‘Air Wedge’ in the heel, a unit that ‘improves shock absorption by 12{a0ae49ae04129c4068d784f4a35ae39a7b56de88307d03cceed9a41caec42547} over an EVA wedge’, where your everyday runner needed it most. The name of the shoe? The Pegasus.

Four decades later, the Pegasus remains a stalwart of Nike’s running stable, routinely selling more than some of Nike’s competitors’ entire lines. Since its introduction, more than 160 million pairs of the workhorse with wings have flown around the world. While other shoes have come and gone, offering more speed, more cushioning or a more barefoot feel, the Pegasus has remained a favourite for generations of runners, not least for its longevity on the road. As the first Pegasus ad put it, ‘Never will so many own so much for so little.’

The X-Factor

Technological innovation in running – always looking for something faster, bouncier, more responsive – was woven into Nike’s DNA by Bowerman himself. But Nike’s genius has always been to combine innovation with sometimes provocative marketing – and to work with some of the biggest names in running. Of course, since baseball players appeared on cigarette cards in the late 19th century, companies have been signing cheques to athletes for their endorsements, so no one would claim that Nike invented athlete sponsorship. But that the brand has redefined that relationship is undeniable.

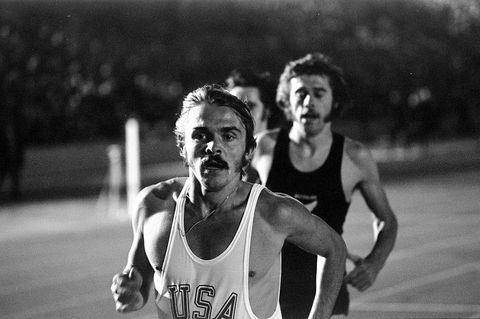

Oddly enough, Nike’s first signing was not a runner but a tennis star – the legendary Romanian Ilie Năstase. But Nike’s second athlete was infinitely more significant – Bowerman’s star pupil and US track legend, Steve Prefontaine. Though his life was tragically cut short at just 24 years old, ‘Pre’ is still venerated today, with Knight describing his spirit as the ‘cornerstone of this company’s soul’ and a building named in his honour at Nike’s corporate HQ in Oregon. ‘Pre preached Nike as gospel,’ wrote Knight, ‘and brought thousands of new people into our revival tent. He urged everyone to give this groovy new brand a try – even his competitors.’ What Pre gave Nike was that most valuable commodity: cool.

From Pre onwards, Nike has also relied on the feedback of its athletes, with designs constantly tweaked to suit their needs and guide its quest for the fastest, most comfortable running shoes. But Nike’s relationships with its athletes have also helped to fuel fundamental changes in running. By the late 70s, female athletes were increasingly frustrated with the status quo, with still no distance races for women in the Olympics beyond 1500m. So, in 1979, marathoner and world- record holder Jacqueline Hansen teamed with others – including Nike athlete Joan Benoit – to form the International Runners Committee to lobby for inclusion. Nike threw its weight behind the campaign, running full-page ads in running magazines calling for a women’s Olympic marathon. Despite resistance, these efforts paid off, and in 1984, the 3000m was added to the women’s programmme at the LA Olympics along with the marathon, which was won by Benoit.

It’s easy to be cynical: backing campaigns is a sure way to generate publicity, and no one can ignore Nike’s moments of controversy, from criticism of factory conditions in Indonesia to its treatment of signed female athletes through pregnancy. Yet Nike’s influence has also helped push through change in running – and in the wider world, too. In 1995, an early ‘Just Do It’ campaign featured long-distance runner Ric Muñoz running over stunning trails and sharing his weekly mileage and 10 marathons a year. Only at the end is the powerful punch: his HIV-positive status. Aids activists applauded the ad, saying it helped remove some of the disease’s stigma.

Back to its roots

In 1992, Knight told an interviewer, ‘From the start, everyone understood that Nike was a running shoe company, and the brand stood for excellence in track and field. It was a very clear message, and Nike was very successful.’ Yet by the turn of the millennium, Nike was no longer anything as simple as a running shoe company: it was a sporting behemoth, a marketing powerhouse and a global brand. And that shift arguably took them away from the original core market.

Perhaps it was a sense inside Nike of needing to reconnect to those roots that led to a significant investment into grassroots-running activities from the early 2000s. Nike has always been a presence in big elite races, but putting on its own mass-participation races became a much more direct way to talk to, and support, runners. From 2001 to 2008, Nike London races challenged runners to ‘Go Nocturnal’ or ‘Run A Year’, while in 2013 to 2014, the all-women We Own the Night series took over European cities.

Nike was able to reach out and connect with runners not just in the real world, but virtually, too, with the launch of the Nike Run Club app in 2010. Such is the reach of the app that there have since been more than 75 million downloads, 1.6 billion runs started and 48 million unique users.

At the same time, Nike was starting to identify and support running crews – new, urban running groups with a more diverse demographic than traditional running clubs. From Run Dem Crew in London to NBRO Running in Copenhagen or Black Roses in New York City, crews attracted runners who hadn’t seen themselves represented in the sport before. With a young demographic full of energy, they were also, frankly, a lot cooler, which began to shift the image and perception of grassroots running yet again.

Sponsorship deals come and go, crews, clubs and athletes switch between brands, but Paula Radcliffe’s relationship with Nike is one of the most long-standing in sport, and it has given her a deep insight into how the brand works with athletes. The former world marathon record holder signed with Nike in 2000, and in keeping with the company’s ethos of involving its elite athletes in the research and development process, from the beginning she was actively involved as a shoe tester.

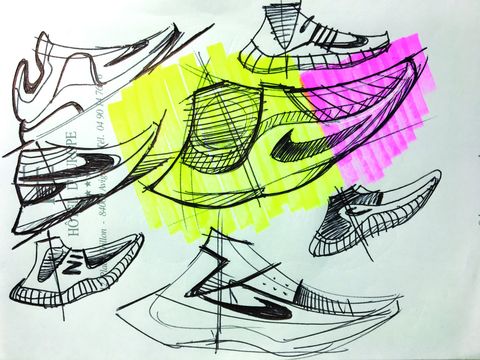

‘Around 2001, 2002, we started working on the Zoom Marathoner,’ Radcliffe recalls. ‘So I actually got to design my perfect shoe around me. I can’t think of one designer who ever made me feel that I couldn’t be completely honest. And I’ve gone back and said, “This is rubbish…” And that feedback would absolutely be taken on board and acted on.’

Those shoes helped Radcliffe break the world record by an astonishing margin at the 2003 London Marathon, clocking 02:15:25 and slicing three minutes off her previous time. It was the epitome of the Nike model: make a shoe perfect for the fastest runner in the world, then filter it down to the mass-participant runner. After all, who doesn’t want to run in the fastest shoe in the world?

Following the science

Whether you’re amateur or elite, performing better is the common goal. And if technology can help us do that, it’ll sell. These days, it’s common for shoe launches to be studded with facts and figures on how they can improve your economy or reduce fatigue. But way back in 1981, the Nike Mariah was the first shoe to be explicitly marketed using science and lab testing. Indeed, the 1985 Nike catalogue said, ‘Tests reveal that running in the Mariah reduces energy expenditure by 2{a0ae49ae04129c4068d784f4a35ae39a7b56de88307d03cceed9a41caec42547}.’

These days, Nike has its own labs and testing facilities. Tony Bignell has worked at Nike for more than 20 years, including 10 as VP of innovation in footwear. He laughs when he describes Nike’s LeBron James Innovation Center, one of the largest sports science research labs in the world. ‘This mix of creative dreamers across so many diverse disciplines – behavioural scientists, materials experts, engineers, designers – are focused on the singular goal of listening to and serving our athletes. When their individual excellence comes together as one, that’s when the magic of Nike happens.

‘The beauty, I think, is when you can pull everyone behind listening to the athlete,’ he says. ‘Let’s obsess [over] what they say. Let’s obsess on making them better. The mission is really simple – make athletes better and then make the world better for athletes. That’s what you’re trying to do.’

This was the ethos behind the Breaking2 project: an idea not simply to create a shoe that would help athletes run faster, but to give it an actual, measurable success/failure metric. Although the marathon world record was inching slowly down, it was still a fair margin over the two-hour barrier. To knock those minutes off, you would need one hell of a shoe. You’d need, really, to reinvent it. And you’d need the perfect athlete to test it – then race in it. Luckily, Nike had the latter already.

From his bedroom in Iten, Kenya, training for what will turn out to be another world record in Berlin, Eliud Kipchoge muses over his relationship with Nike. ‘I have to say that it has been a tremendous journey,’ he says. ‘I’ve been with Nike for 19 years now, but the best moments have been in the past 10 years when I’ve really been involved inside the company, testing the shoes, testing the apparel. I’m really happy to be involved in doing this work, from the bottom of my heart. When we started [the sub-2:00 project], it was very small, but then it expanded and where we are now… I can say that it’s a game changer.’ If anything, it’s an understatement. The Vaporfly, and subsequently the Alphafly, have changed running history, worn to set official world record after world record as well as to break that two-hour barrier.

But it has been a long journey. The project started as early as 2014 with a first prototype, essentially a heel-less racing flat with a carbon fibre plate. Test runners hated it. In 2015, foam was added – a huge wodge of super-light foam usually used in aircraft insulation, which they named ZoomX. Embedded in that was a carbon fibre plate. In Kenya, Kipchoge was giving his feedback. He describes a process of constant tweaking: ‘I try the shoes, I send my honest feedback, and again, and it’s an interesting journey – a happy journey!’

As always with Nike, says Bignell, you centre on the athlete. ‘The model has always been start with a Paula or an Eliud or whoever may be at the top of the pinnacle. Because they know their bodies really, really, really well,’ he says.

The original Breaking2 attempt on the Monza racetrack in Italy in May 2017 ended in a rather glorious ‘failure’ – Kipchoge ran 2:00:25. He was watched, in an interesting demonstration of Nike’s grassroots to elite influence, by runners invited from various Nike-supported crews from around the world. But in 2019, the ‘impossible’ barrier was broken by Kipchoge in Vienna, clocking 1:59:40 while wearing the prototype Alphafly, with two Air pods under the sole for even more energy return.

Then, in September, he wore the latest Nike Alphafly to take 30 seconds off his official world marathon record in Berlin for a time of 2:01:09. The step change brought by carbon plates is undeniable. Some may mutter about ‘shoe doping’, but without Nike’s support of elite athletes, and events, be it championships or projects such as Breaking2, the profile of running would be unimaginably different. And considerably slower.

Next steps

Given how long Breaking2 had been under way before we even heard of it, it’s tempting to imagine a group of designers locked in a secret Nike lab, working on the next leap forwards. Perhaps even more cushioning, even greater stack heights? Bignell laughs. ‘All these things constantly change – that we’ve gone big and high has a lot to do with protecting muscles,’ he says. ‘But if you could do that, if you could offer the same protection and it was thinner and lighter, then you would.’

Asking Bignell about Nike’s next big goal elicits a surprising answer. You might expect talk of more records, but no. ‘We spend a lot of time going from, okay, how do you serve a Kipchoge, but then how do you help my mum get around the block with her dog? I just want people to move,’ he says.

He also raises an intriguing idea, sure to raise the hackles of running purists. ‘[Electric bikes] are brilliant because there’s always a reason not to go on your bike, but you have this thing that can make it easy. And I would love to get there for running. Obviously not for competitions, but just to keep everyone moving.’ Self-propelling running shoes? It sounds sci-fi, but then in 1972, carbon fibre plates would have sounded the same. ‘If you don’t push the edges and don’t fail, you’re never going to learn,’ he says. ‘It’s never linear; it’s always three steps backwards, two steps forwards. You want to win, and you do that by dreaming audaciously.’

For Kipchoge, part of the dream is finding ways to make it easier for people to fit running into their lives. ‘Our mindset is to make the person recover very fast, whether they run that marathon in five hours, four hours, three hours,’ he says. ‘We want to help that person take care of their muscles, so they can run for five hours, but then tomorrow, they can then do their own hobbies or their own work without any pain.

‘The aim personally, and with Nike, is longevity. We want people who are running for 10 years, 15 years, 20 years or more, and enjoying their runs every day. I want to work with Nike to spread the gospel of running,’ he says. ‘I always say if you want real freedom in life, it’s in running.’

It’s a message that will resonate with us all, and whatever the logo on the shoes we choose to wear when heading out to find that freedom, we owe a little something to Nike for its part in creating the running world around us. In another 50 years from now, we can be sure that world will have evolved in ways we can’t yet imagine. And we can also be sure that Nike will have had a hand in shaping it.